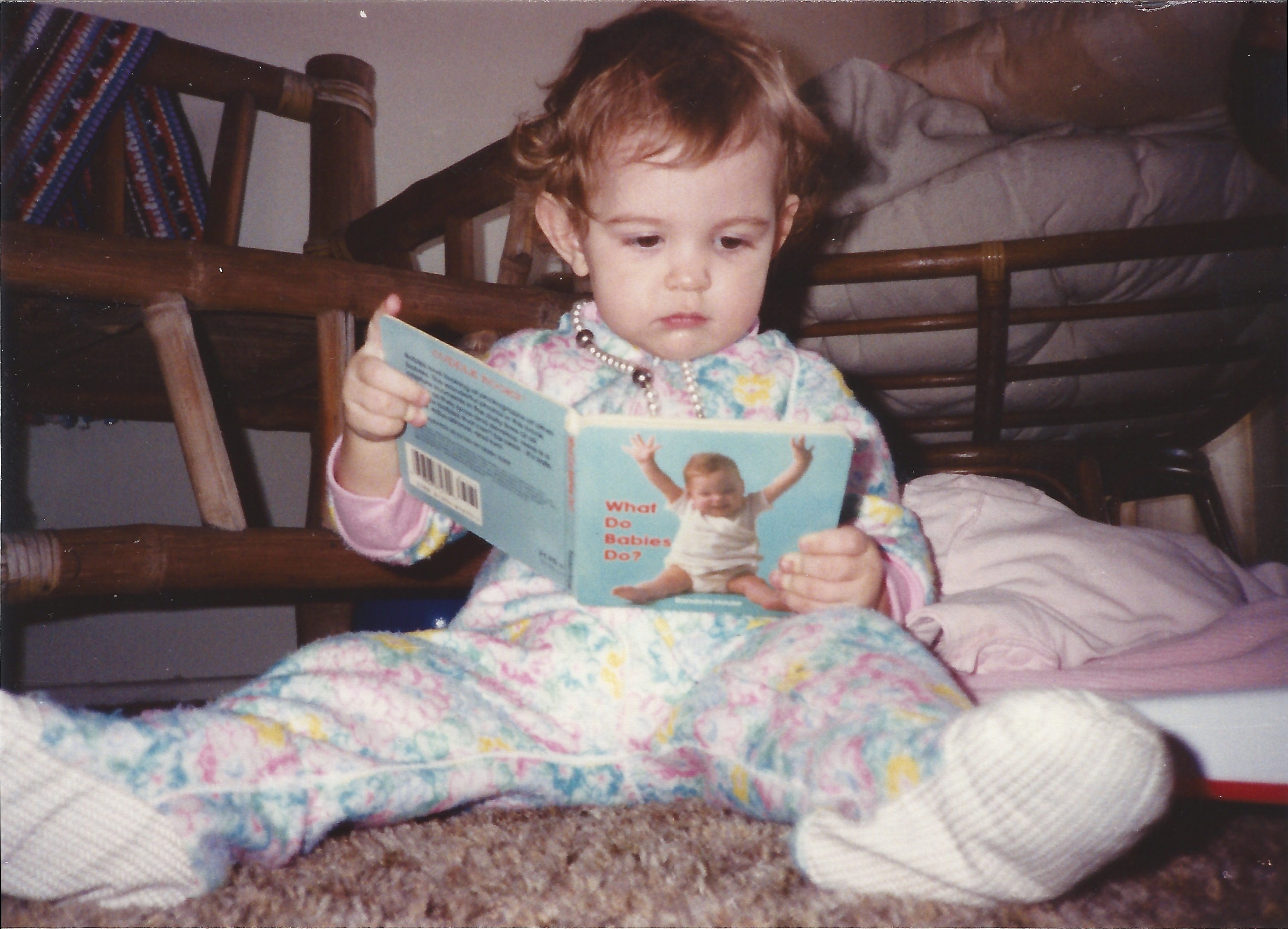

When I was a young mom, my step-mother Nancy gave me a copy of “The Strong-Willed Child” by Dr. James Dobson. This book was so helpful; it opened my eyes to the fact that I didn’t know what the heck I was doing. I read it and read it again, taking notes on how to appropriately hedge-in my precocious, curious, stubborn little Daisy – without destroying her spirit. With that book, my ignorance about all manner of life’s challenges was exposed. Thus began a fifteen-year habit of referring to self-help books for advice on parenting, spirituality, love and marriage, and healing the wounds from childhood.

The last parenting book I bought was by John Rosemond, who wrote a column syndicated in our local paper. I found “Teen-Proofing” while perusing the parenting section at Barnes & Noble. I was entering the season of parenting with Daisy where I felt like I had no influence on her decision making. I knew I could find the solution to my problem at the bookstore. I recognized his name, I appreciated his column; I bought his book.

I read it, and it was helpful. I learned some tips on how to give my teen privileges, stop worrying about every little detail of her life, and utilize grace in our relationship. I can’t say that I executed what I learned in a commendable way, but I did learn. The most impactful information, though, was in the introduction.

First, he told me, (paraphrased from my five-years ago memory) “You care about your kid. You went to the store and looked for help about parenting because you care about doing the right thing. You are a good parent because you are worried you might be a bad parent.”

Hmmmmm.

And the zinger: “You were a teenager once. You did stupid things. You probably caused your parents much anguish. Yet somehow you managed to learn from mistakes and get your stuff together to reach this point: you are now a grown-up who is a good parent. It didn’t work out so bad, did it? Why do you think that your teenagers don’t have the right to do things the wrong way, in order to learn why it’s wrong? Why do you think you have to be so good that your own kids skip this crucial developmental step?”

Here is 2010-Tina’s response:

“I’ll tell you why, John Rosemond. I’m not supposed to be a good parent. I’m supposed to be a perfect parent. My kids are supposed to blossom and grow under my guiding hand and are, in turn, going to become wise without testing, virtuous without temptation, fulfilled without desire.”

That sounds pretty ridiculous to me now. But I really did believe that my kids were going to make “the right” choices because they loved me, trusted me, and wanted me to be proud of them.

And my plan for perfection wasn’t working. My precious Daisy cared less and less what I thought of her, and was slipping away from me. Our closeness was dissolving. So many of the things she had confided to me, I was learning, were only one side of the coin. She had me figured out: she could keep me happy by telling me about the parts of her life that I wanted to hear: she loved her church family, she thought most of her peers were dumb and misguided, she wanted to “wait” for marriage.

Reading what I just wrote chokes me up. After so many years, it still hurts; that in my journey to be the perfect mom, I marginalized my daughter’s burgeoning opinions and desires, trying to overshadow them with my own ideas about what was right. She and I missed out on the opportunity for true trust and intimacy. I can only imagine the betrayal she must have felt. And when things got really hard for her and the world became unsafe, when she needed comforting arms around her that told her she was loved despite anything, mine weren’t there. She couldn’t, and didn’t, come to me.

Here’s Tina, now:

“I don’t care about being a perfect parent. I don’t care what other people think about me and how they will judge me for not getting my teenager under control. While I may have once wished that you were a peaceful and compliant child, I know who you really are and I accept you. I want you to feel the beauty of freedom. I want you to stretch out, test everything you doubt, shock me, disappoint me, make me cry out to God for strength. But I never, ever want you to doubt your trust in me. I never want you to underestimate my love for you.”

There are other, more insidious ways to harm your kids besides the ones we might focus on, like “Is this a safe relationship?” or “Should I let them see that movie?” or “We’re missing church again because of a soccer tournament!” The worst thing you can do is tell them that you love them unconditionally, but model judgmental haughtiness towards the world. The worst thing you can do is place a high value on elevated ideals without showing moment-to-moment grace for the very real way all people behave, even good parents like me. Even good kids, like Daisy was. Because being good doesn’t mean you don’t make mistakes.

Perhaps being “good” is more about acknowleging your bad decisions, then apologizing. And then making the choice to do things differently.

Thank goodness that Alyssa, Zander, and I have a different relationship than the one I unwittingly fostered with Daisy. Thank goodness I can find the humility to tell Daisy “I’m sorry I didn’t figure it out sooner.” I see the parallels between my relationship with my precious children and that of my Creator with me: I am welcomed, loved and cherished. Thank you, God. And thank goodness I found John Rosemond’s book – the one that ended my self-help habit. (It really is a super book. If you are confused about how to set limits for your teenage kids, I highly recommend it!) Now, instead of reading about how to have a better relationship, I am free to just be real and have one. I’m not living in a family where everything is awesome and we all get along. We fight and bicker, share our opinions, get our feelings hurt, apologize, and make one-another laugh. Sometimes I’m disappointed by their choices, and other times, I am amazed at how wise they can be.

Like other parents, I care tremendously about my kids and the decisions they make. When things don’t work out for them, it hurts me. Most pain inspires you to do things differently next time. This pain, though, requires patience. It is the other side of unconditional love, and I’m not going to do anything to change that.